In 2003 an art critic Lukasz Gorczyca published on his blog an article about Polish sculptor Wladyslaw Hasior (1928 – 1999) and public sculptures located in Elblag, a city in northern Poland. Below there is a part of this article and I only add that many of the artworks mentioned there are (unfortunately) still falling into decay.

Lukasz Gorczyca is a curator, a writer and a co-owner of the Raster Gallery.

Blog [PL] Gallery [PL/EN]

Hasior – an extraordinary sculptor

Wladyslaw Hasior, who had died few years ago, was both an artist and a person fascinated by the provincial, church fete material culture. He belongs to a group of artists who had been abandoned by Polish culture about two decades ago. The value of his works has been called into question when some pointed at Hasior’s sculptures in which the legend of people’s power lived on. Perceived as an artist from the “ancien regime”, a star peculiar to the art of Polish People’s Republic. He slid (was put in fact) into the shade on the Polish art scene. That simple, or rather simplistic, histo-cultural mechanism had worked perfectly for yet another time, causing a factual harm. As Hasior, and his, to some point insane, works deserve to be treated absolutely seriously nowadays. The label of a dusty museum relic is somewhat too trivial while referring to works that have had shaped the Polish landscape (both mental as well as physical) with verve and imagination. Apart from numerous, though not necessarily displayed, works in museums (we recommend Zakopane and Wroclaw) Hasior left a number of works in public space, primarily monuments. Ranging from plain stone works (like the monument of the Tatry Mountain Rescue Team in Zakopane), to impressive sculptures incorporating water and wind (monuments in Kuznice and Czorsztyn), to experimental forms like Monument of the Shot Hostages in Wroclaw – cast in concrete in moulds dug directly in the ground and then set on fire. Fire was also the favorite element used by the artist in his “processions” and other, ephemeral, projects in public space. It was also fire that had appeared in Szczcin in 1975, when on the slopes surrounding the castle Hasior “unveiled” his new work “Firebirds”. This impressive and prodigious installation made of iron and sheet metal remained in Szczecin for good. After a few moves in the 90’s it eventually landed in Kasprowicz park on the outskirts of city center. That was the moment when its slow but gradual degeneration began.

Elblag – the untapped potential

Modern sculptures, monumental metal forms placed in city space or in parks park are, just like electricity poles, a perfect target for the junk collectors. A few years ago in Elblag those people looted a large part of the famous piece by Henryk Morel, which overlooks the city from a nearby hill. It is one of a few dozen of works made within the framework of the Biennial of Spatial Forms, held in Elblag in the 60’s. In many ways this event was pioneering on a global scale, what is more, it all resembled a utopia that came true. The Biennial was realized under the patronage of ZAMECH, the local industrial plant, and artists had worked along with plant workers building their works from scrap material. In the center of Elblag one can still see numerous modern sculptures by leading Polish artists of the 60’s. Their condition is fairly good – obviously they are being repainted every now and then. Yet for the time being, not only junk-collectors but Elblag officials as well, may call this situation “the untapped potential”. While this unique collection could be easily turned into both tourist and artistic attraction. And the effort is nominal: to prepare a comprehensive catalogue (each year, about a hundred young people graduate in Art History in Poland), print leaflets and town maps including itinerary, and conserve the sculptures. One could organize a special art project and invite contemporary artists to dust the beautiful, modernist Elblag utopia.

+++

The Foreign Correspondents project is probably going to be a melange of points of view. Let me present two of them: one by the ancient historian Polybius and another one by Gay Talese, an American journalist.

NOW IN EARLIER times the worldâs history had consisted, so to speak, of a series of unrelated episodes, the origins and results of each being as widely separated as their localities, but from this point onwards history becomes an organic whole: the affairs of Italy and Africa are connected with those of Asia and of Greece, and all events bear a relationship and contribute to a single end.

Polybius (died 118 BC), on the rise of Rome (translated by Ian Scott-Kilvert)

D. Shankbone: What do you think is the reason there is this collective idea to give Americans a certain view of a place or a people that is not necessarily accurate? I think Iran is another good example, where we are consistently fed images and notions about a people and a culture that arenât really accurate.

G. Talese: Or fair minded.

DS: Or fair minded. But the reality is far more interesting than the same stories we

are consistently fed.

GT: Well it involves more work. I think most journalists are pretty lazy, number one. A little lazy and also theyâre spoon-fed information, such as the weapons of mass destruction back in 2003. Itâs easy. There are all these lobbyist groups, these special interest groups. Each of them has a position with regard to Taiwan, for example. The anti-China lobby is very strong. Whether itâs the gun lobby or the Israeli lobby or the Taiwan lobby, whatever the hell it is, you have these people who create a package of news, develop it as a story line, a scenario, and they fi nd, as Mailer once said about the press, that theyâre like a donkey. You have to feed the donkey. The donkey every day has to eat. So these people throw information at this damn animal that eats everything. Tin cans, garbage.

Gay Talese on the state of journalism, Iraq and his life. David Shankboneâs interview with Gay Talese. October 27, 2007

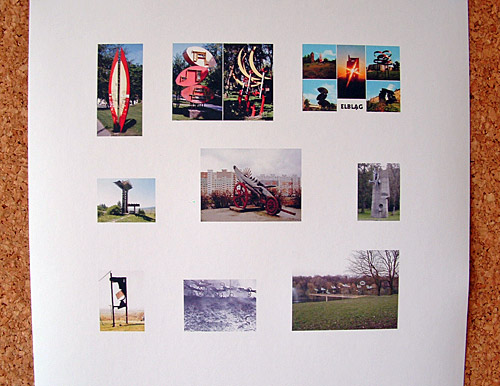

Top row: Public sculptures in Elblag, Poland.

Middle row Wladyslaw Hasior’s monuments, all in Poland: “To those who die setting up a people’s democracy in the Podhale region”, Czorsztyn, 1966 | “To those who fought for the Polish character and freedom of the Pomerania region”, Koszalin, 1980 | “To those who fought during WWII for freedom of the Podhale region”, Zakopane

Bottom row: Henryk Morel, sculpture in Elblag, 1967 | Wladyslaw Hasior, Unveiling of the Firebirds sculpture, Szczecin, 1975 | The Firebirds sculpture in 2008, Szczecin